It seems clear to me that these last three articles, under the heading “the end of popular culture?” are directly dealing with issues of the embodied experience. The way that the body can naturally be sexualized, ethnically classified, hierarchically organized and gendered exists in all these articles. Part of this embodiment paradigm is the idea of theater which is explained well in both the Gómez-Peña piece and the Beltrán piece as well. Clearly how one uses their body dictates to some degree how theatrical they are, or how they are aware of the public domain as theatrical. It seems apparent that both Subcomandante Marcos and Jennifer Lopez have learned to use the media to their advantage, at least principally.

I’m also beginning to wonder what role the media are playing in this pop culture arena. The Canclini article from last week posits them as part of the production of popular culture, but this weeks articles portray the media as a tool to be manipulated by those who are actually creating popular culture.

I’m actually really surprised that a whole academic article has been written on Jennifer Lopez’ butt….Seriously. It seems strange. But if the body is the site of struggle as the title suggests, it’s worthy of some analysis. I was thinking about the production of culture as well, and how in the Jennifer Lopez article it seems to be a process of both her and the media, or her agent anyway. No longer is this production in the hands of white, male elites. A latina woman can be popular culture and can have the power through her body to alter conceptions of the popular and the beautiful.

I was troubled to read that Román-Velazquez comments that salsa has become associated with a pan-Latin identity. I wonder how Latin people see that. I would argue that there are many things associated with this pan-identity, but that salsa is just that to some.

Bodies!! Get your bodies!! All different colors!! Get ’em before they’re gone!

March 31, 2009what exactly does he mean by hybrid? Is he talking peas?

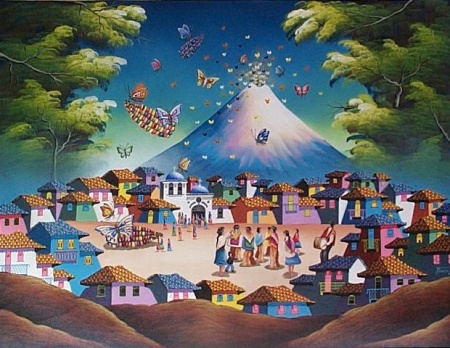

March 26, 2009This whole idea of hybridity, proposed by Canclini seems problematic to me. Not necessarily the way I had conceived of hybridity before, in thinking about different types of pea plants, and the outcomes of their cross pollination, but in the way that Canclini seems to posit it at a meeting of two distinctly different and contradictory ideas. I get a strong sense that he sees the modern and folkloric as contradictory as well as the modern and the popular. What I fail to completely understand is how this is the case at all. Having read Williams we know that those who are in the countryside welcomed the advances of technology brought along with modernity. And in many ways, the country side was home to some of the most modern advances. In terms of the popular and modern, he seems confused. Clearly what is popular can be modern, and can be hegemonic in its own right. Look at futeball, or even certain eating practices. Whether they began in the city or not seems beside the point. They are things appropriated by massive groups of people, or initiated by them, and not by elite culture at all.

Interestingly though, I see how Canclini can make a case for hybridity using the countless examples he does. Humor, collective memory, successful production of handicrafts, graffiti, mass media, political upheaval, popular expressions of traditional religions, migrations, artistic movements and tourism, for example all contain examples of the hybrid or a blending of the six ideas he presents at the beginning.

I disagreed with his process of modernity however, even if it was discussing the basis for his concept of hybridity. I disagree that the modern=cultured=hegemonic, and would counter that the traditional can = cultured, and that often the subaltern can = hegemonic. I keep thinking back to his section on the massification of culture and the way that the subaltern often became quite powerful in activism and protest. Groups like the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, or even the people in Eva Peron’s piece idealize the power of the supposed, uneducated, uncultured masses. I suppose the massification of culture can be an example of hybridity, but I don’t see it in contrast to the modern, cultured or hegemonic necessarily.

The collective whole…Taking a hit for the team…The nation that is

March 17, 2009 Despite the length of this weeks readings, they were absolutely more enjoyable than normal. Perhaps it was because of the fact that for once we were reading about something that is undeniably considered (despite the seemingly elusive nature of the term) “Latin American popular culture,” and is considered as such by most people from Latin America. As we read, if you are Brazilian, you know about futebal/soccer. Alex Bellos’ writing was engaging, and narrative. Through the different vignettes he writes, a few things become apparent. Bellos develops symbolism through his understanding of the game. (loss of 1950 World Cup was an affirmation, correct or not, or Brazil’s collective understanding that they were fractured nationally;Pelé and Garrincha symbolize Brazil’s greatness and racial make-up) Whether he is merely elaborating or elucidating what he sees occurring in Brazil, I’m not sure. But it’s clear that certain things become metonyms for Brazil and their collective character. This idea of the collective also permeates much of what Bellos writes. In fact it seems that futebal/soccer has the ability to contibute to the creation of “imagined communities.” If not imagined communities, than the concept of nationalism, collective memory, and collective guilt. Futebal/soccer also becomes a conduit for discussions of race, gender, nationalism, and memory. The chapters selected for our reading also demonstrate the way that futebal/soccer has permeated so many parts of Brazilian everyday life. Not only does the jersey’s signature yellow color come to denote Brazil globally, but people around Brazil see visual indicators of the game’s importance to their country in the titling and construction of many buildings and “monuments” named after Brazilian futebal/soccer stars. The chapter, “The Fateful Final” was especially helpful in understanding the mentality of futebal/soccer fans, and the reason why the game may matter so much to them. The collective sense of failure and dejection Brazilians associated with the 1950 World Cup loss followed such a strong sense of collective hope, and renewal following their military dictatorship. In a country divided by race, and with huge economic disparity, diversion like futebal/soccer can come to mean a lot of lost happiness if your team loses.

Latin American telenovela as Ortega writes comes to be a representative of the changes in Latin America through its ability or tendency to remain culturally and socially relevant to its viewers. These shows become arenas to discuss issues of race, class, gender, sexuality, machismo, and the quotidian. Interestingly, as Ortega denotes the difference between telenovelas and soap operas it almost becomes a distinction between values or ideology. The soap opera focuses on money and sex. Whereas telenovelas focus on the continuation of family. Could these shows come to stand in for nationalist values transnationally? What role do they play in shaping relationships between countries? I loved seeing the reference to telenovelas and their descent from the folletíns we read about in Rowe and Schelling. The other idea that struck me from Ortega’s piece was the idea of telenovelas as cathartic. Perhaps this is a modernist perspective of Latin America, but my understanding is that a number of countries from the region have been made poor, and as such have large numbers of people living below the poverty line. This indicates to me that the idea of catharsis, or escapism may play a role in the popularity of the telenovela. People who struggle to provide the everyday necessities are able to vicariously live through the stories of their country’s telenovelas. In the same way that Brazilian futebal/soccer can be collectively shared by people from all walks of life, the telenovela can do the same in other places.

Can any of this be synthesized anyway?

February 24, 2009I’m still reeling and really have no idea what exactly can be, should be, will be, was and is classified as Popular Culture, especially in an area so undefinable, diverse, broad, multicultural, and flexible as Latin America. But I suppose it is exactly these things that we are meant to understand better through this semester’s readings so far. The idea of popular culture as not being considered a coral reef, gradually changing over time as is suggested by Keesing. Perhaps the idea of culture as a journey comprised of the ordinary, everyday, educational, or working class is a more accurate representation. I identify more with the idea of cultural development as a journey, as opposed to the slow unnoticeable accumulation of things. There are likely examples of both types of culture, however it seems that both are forms of process.

I suppose there is some connection between the people and their culture, or the culture they consume, if culture is something to be consumed at all. Eva Peron, and her version of populism provide one example of the people as the descamisados, workers, women, exploited and suffering. She contrasts this idea with those in the oligarchy, or the military. Interestingly though, I find it hard to categorize her as a member of the group with whom she so enthusiastically tries to identify. Borges’ article sheds light on the idea of the people as well, but from a different perspective. From Rowe and Schelling the power of the media in all its forms seems the most relevant to me. Not only the power of the written word, but the way that music, dance, drama and oral stories come to be popular culture, or forms of it. The historical narrative they supply provides a good background to contemporary popular culture and what is loved and abhorred now. They seem to embrace the idea of culture as a process more than an explosion or apparition, as does Williams. Reading what I see as examples or representations of actual popular culture in the works of Arguedas and Asturias was interesting. Through the works, ideals, values and discourses are apparent. I’m interested to better understand the way certain discourses permeate their writing, even if they consciously felt they did not ascribe, construct or fit into them. Having discussed Vasconcelos in other Latin American related courses, I was glad to finally read a sample of his famous work. As problematic as it may have been, it provided an interesting example of thought and race from the 1920s. The racism he includes in his work seemed normalized and expected. His class, socio-economic position and gender are highly present in his work, and contribute to why we might find problems with what he wrote presently. Wade’s reaction or counter point that perhaps culture, race and mixture can be better understood as embodied experience was more in line with my personal opinion. I liked that he was able to acknowledge that people can find commonality in their differences within constructs of supposed homogeneity. The idea that a nation can be both homogenous and heterogeneous at once seems paradoxical, but was clarified when Wade wrote about the woman who was a mulatta. When asked whether she identified with black or white parent better, she answered that she was neither. This avoidance of classification alters conceptions of culture creation, nationality and identity.

No one perspective can come to represent such a diverse and changing area such as Latin America. The people can not be seen in one light, nor can popular culture be classified in only one manner. The process of creating and defining that culture is not unidirectional, nor is it always at one speed, or by one group. Identity, race, class, gender, education, sexuality and space interact altering what is considered culture and what is popular about it.

Magical Unrealism? Did Atlantis Exist?

February 10, 2009

I don’t know about everyone else, but I feel like we’re reading some form of magical unrealism this week. I have a ton of problems with a lot of what he says, but I think we’re supposed to try and understand the idea of mestizaje he’s proposing. If that’s the case, I hope it isn’t the form that was adopted in his home country. Also, I wonder what Jon thinks about Vasconcelos’ saying, “the English had to be satisfied with what was left to them by a more capable people” (10). The entire piece is laced with abominable comments that made me say, “WHA???” out loud. Apparently the fact that Napoleon sold Louisiana to the Anglo-Saxon/English/Americans ended up being the reason they were able to also take California and Texas from Mexico. It sounds like he’s never ever heard of Manifest Destiny…I wonder if that ideology had any impact on the taking of Texas and California.

But the point of this piece is the mixture that he envisions, and his concept of races. He seemed to see the world as “a conflict of Latinism against Anglo-Saxonism; a conflict of institutions, aims and ideals” (10). The Latins suffere from caesarism, while the Anglo-Saxons tend to be lacking vigor. Despite claiming that mixing can strengthen the fifth civilization he envisions, he still places the “colors” in a hierarchy, and labels the whites and reds as civilizations, while he labels the yellows and blacks races. Inherent in much of his language is a hierarchy of power through color. I have so many issues with his work. I suppose it is reflective of the time he was writing. I’m not so sure though. I have problems with how he envisions this fifth race is going to come about. He believes a taste for beauty will encourage the development of a handsome race. He also comments, “America was not kept in reserve for five thousand years for such a petty goal”(18), referring to it being used by the Anglo-Saxons to replicate a Northern Europe. His belief in predestination is interesting as well. It’s also interesting to me how he personifies History. It’s as though History is itself a force with which to be reckoned, with the agency to organize and disorganize. This post is disjointed, but there are so many issues at stake in his piece here. Identity and self identification, belonging, racism, inherent superiority, the power of the environment/nature, esthetics, romantic notions of humanity, and an overall sense of the unrealistic.

Wade’s approach to mestizaje seems more realistic in that he acknowledges the dualities present within it, and is able to see them as part of the mixture as opposed to a problem. His approach to mestizaje as a lived or embodied experience makes it easier to understand in tangible ways. Using the examples of people and music are things more easily relatable. Anyone who has a history is able to think about identity and how it is negotiated. In this way, Wade makes headway. It seems realistic that within any form of mixture among people, there will be elements of inclusion and exclusion, as well as sameness and difference. Wade tells us that, “the concept of mestizo includes spaces of difference as a constitutive feature, while also providing a trope for living sameness through a sense of shared mixed-ness” (249). I identified with this idea of finding sameness in the difference or mixture itself. As an idealist I prefer ideas that can acknowledge difference, but accept them at the same time. Thats just how things can be. After reading Wade I questioned how much ideas of mixture actually inform people’s lived experience though. How much to they recognize what they are living as part of an ideology? Hmmm….? Anyway…this might be too much of a rant…See you in class.

magical realism…

February 3, 2009

yesterday, today and tomorrow…love is entirely contained in everything

February 3, 2009 Miguel Angel Asturias writes with what I consider a form of magical realism…Perhaps it might be called romantic surrealism. I’m not sure how to classify it or what his agenda or message is. I found the legends engaging because of the language and the imagery he was able to create in my mind. Overall though, I wasn’t entirely sure what was happening in my head. What I was reading felt like I was picturing a stream of disconnected dreams. Images of ancient cities, 19th century zocalos, Maya steleas, natural beauty and fantasy worlds went through my head. I really like the book 100 Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and read similarities here, but I didn’t as much sense a narrative with Asturias. I couldn’t help wondering what a Maya person would think reading these ‘legends.’ Would different images with symbolism pop out to them?

One common theme that seemed to come up was ideas about the past, present and future. The singing tablets legend included the line, “by speaking, I make the present, by keeping silent, I make the past, and by speaking in my sleep, I make the future” (85). The Legend of the Dancing Butchers contains the line, “This woman has yesterday in her ears, the present inher mouth, and the future in her eyes…” (117), as wel as, “the intact body of the one who in life had ears which heard rumors of yesterdays, ember lips which ignited the present, and eyes filled with divinations of the future” (126). These lines indicate some sense of continuity to me, but I question what his agenda is in perpetuating this concept. Does he acknowledge the Maya present through time?

Part of what seems a part of Latin American culture, as demonstrated by these reading is the idea of the parable, legend or story. Either as a form of oral history, as a means to convey morality or social norms, or for entertainment. There are probably other functions of these kinds of pieces but I don’t know yet what they might be. The Pongo’s Dream made me evil laugh in my head…It’s nice to see an underdog overcome the big dog…Strong moral implications in that story as well.

culture as an object? as a process?

January 27, 2009Rowe and Schelling’s article, The Faces of Popular Culture does a remarkable job of communicating just how much the development of culture is a process. In some instances it seems that what functions as popular culture does so as a result of hybridization of syncretism. The popularity of a number of cultural elements seems to be increasing in terms of how ideas and information can be exchanged between various sources. These included the rural and urban, literate and illiterate, indigenous and European, and modern and traditional. This is to say that these systems are not highly bounded, but the opposite. What seems to have contributed to the formation of certain forms of popular culture in Latin America is the way in which the modern and traditional or indigenous and European have been able to appropriate elements from each other in the formation of new, and more inclusive cultural elements. In their discussion of resistance and conformity they caution us that, “It is risky to let them become an exclusive paradigm” (105). This idea of exclusivity directly contradicts the idea of transculturation and the multi-directional exchange of ideas from different systems of thought.

Mass media play a huge role in the dispersal of popular culture, or any culture and can often be considered the “make it, or break it” element of something’s popularity. Both contemporarily and historically media and technological improvements have had compelling effects on culture. With the rise of the record and recording industry the spread of music and certain up and coming genres is possible. The printing press, though originally a “toy” of the elite enabled the spread of ideas. Computers and the internet have served to increasingly shrink the proverbial size of our ever expanding media and cultural world. Much of Rowe and Schelling’s article deals with elements that can be considered media, and through their appropriation by “the people” they become traffic on the mass media highway. Traveling along this highway is a process that often alters them from their state at the beginning of the journey. This process of cultural articulation is an interesting area of study.

Who are “the people” ???

January 20, 2009Eva Peron’s discussion of “the people” is confusing, particular, exacting and seemingly un-populated. If she claims that her Argentina, in its true essence, is the people then perhaps she should have been more inclusive. Whatever the case may be, this term “the people” is ambiguous to me. Having read the Borges paper as well I feel the term is even more arbitrary. It seems through his narrative in “everyday” lingo he is appealing to the very same people as Eva Perón, or even writing as one of the descamisados.

Perón writes problematically about women in that she is constructing a very particular and specific Argentine woman. While she may claim to be appealing to the people, and their inherent humanity, she seems to be doing so on very exacting terms. She has a highly politicized sense of who the people are. Using her relationship with her husband Juan as a sort of basis for her loyalty and character, she calls for similar outpourings of loyalty and feeling from Argentinians, and the world. Women, according to Eva are to be highly sentient, humble, modest, protectors to men, encouragers, companions to men, students to men, and “like a bouquet of flowers in [their] house” (Perón, 1996: 54). She contrasts these women of the people with men and it seems that men are the calculating thinkers, and women are the emotional hearts.

Borges’ Celebration of the Monster was an appealing read, despite being confused as to who The Monster was. Stylistically it might be considered stream of consciousness, which appeals in that it mimics human thought processes. As to what he is trying to construct about the people, a lot of everyday elements are included. Struggles with other people, protesting a dictator, being tired and about making ones own luck. I get the feeling from this piece that the protagonist is a protester, but can still be considered one of the “people,” despite his distaste for The Monster (who I assume to be Juan Perón). Reading Eva’s piece prior to this one in her calls to the people to be fanatical, supportive of her husband, workers, his surrogate family when she is gone, and overall full of heart could be a contrast to the character in Borges’ piece. Not being many of these things the protagonist of Borges’ piece certainly seems to be one of “the people” despite this lack. Perhaps that is why Eva Perón’s piece was upsetting. She does not include any space for “the people” to question their roles, contradict he husbands ideals, communicate with the government (except through herself as a conduit to the government), or protest. Perón writes more idealistically of “the people” while Borges seems to represent “the people” more realistically with his main character.

Is Culture Ordinary?

January 13, 2009It is interesting to see the connection between the Williams and Keesing articles in how they incorporate “culture” into broader, accessible processes of experience, understanding, learning, reciprocity and creativity. It seems that both are trying to communicate that no “culture” or society can operate isolated or outside of everything in the world. They do however display some differences in their approach to the concept of culture. Reading these articles it seems so obvious that cultural development and what is considered authentic culture would have to undergo various expressions of evolution, and can be involved in a reciprocal process of information exchange.

Williams, in his discussion clarifies that segments of a society or nation, despite their treatment by society’s members, can not be excluded from that culture or nation if they are present. His article was somewhat problematic to me in how he utilized somewhat general or blanket statements. Things like a “good common culture,” or “the product of a whole people” are phrases that seem to act in somewhat exclusive manners, isolating certain groups or essentialize others. What exactly is a “common culture?” And what are the products of a whole people?” He elaborates on ideas of culture only being thought of in certain ways and is effective in arguing that many different types of people and expressions of their cultural ideas comprise “common culture.”

Williams seems to be making some assumptions about what is desired in a society, and what are desired improvements. Doing so casts him into a somewhat colonial dichotomy of the primitive versus the civilized, for example. He seems to want to see social cohesion, and the acceptance of a common culture. It is problematic to me to see how he would engage and include differing religious beliefs, educational imperatives, marriage practices, and political values in the society the seems to be espousing.

I was encouraged to read his opinions on relevance in education because it seems to directly relate to university life now. The “old boys club” of traditional education relies on, what I think is, an outdated, sometimes irrelevant group of theories and perspectives. Requesting that current education reflect what is relevant seems an obvious choice, however the persistence of certain archaic ways of doing things persists.

Keesing’s article on theories of culture was interesting in how it appropriated post-structuralist/postmodern theories of culture as ideals. Also his discussion of how these theories are still informed by more modernist ideas of alterity and dichotomy fit well with Williams’ presentation of Marcus and Fischer’s idea of a cultural evolution. No group, idea or society can act outside or isolated from other with which it interacts. “Cultural situations are always in flux, and cultures are always in a state of resistance and accommodation to broader processes of influence” (Marcus and Fischer, 1986: 78).

The optimistic, unrealistic side of my psyche gravitates to Keesings request that academic disciplines can learn from each other, and reciprocally interact and influence each other positively. Being able to understand how commodities, power structures, and history affect our understanding of the cultural would mean a better academic world overall.